Managing Delhi's Air Pollution: Challenges and Solutions for Schools

Dr. Feroz Khan

A circular issued by the Directorate of Education (DoE) in 2023 mandates that Delhi schools ensure 220 working days. In general, schools in Delhi have three long breaks – like summer vacation which begin in May and ends in June; an autumn break around October; and winter vacation in January, along with other holidays.

In addition to planned breaks and holidays, schools often face unplanned closures, primarily due to winter pollution in Delhi. These unplanned breaks disrupt the goal of achieving 220 working days. Recently, the Delhi government decided to shift primary classes to online mode due to severe air pollution. This is not the first time such a decision has been taken. In fact, in 2016 1800 primary schools were shut in Delhi due to severe air pollution, and since then, similar decisions have been made every winter due to the persistent air pollution problem.

Studies have revealed that indoor air quality (IAQ) and poor air conditions in schools significantly affect children’s health and learning outcomes. Pollutants like PM 2.5 and CO2 not only cause respiratory problems but also impair cognitive abilities such as memory, attention, and problem- solving. Prolonged exposure to such conditions can lead to absenteeism and reduced academic performance.

International Responses to Air Pollution in Schools

Delhi is not the only place where schools are affected by the pollution. A few neighbouring countries of India faces similar problem, though with varying intensity. For example, in 2015, the red alert for smog made Beijing to close schools due to pollution. In 2021, the Nepalese government ordered schools to close when air pollution reached hazardous level. Similarly, in November 2024, the Pakistan government ordered the closure of primary schools in Lahore for a week due to unprecedented air pollution levels.

Apart from neighbouring countries, Mexico has also faced similar challenges, occasionally closing school due to pollution. Yellow dust storms in South Korea often lead to the reduction or cancelation of outdoor school activities. The outdoor activities are related to the physical education and sports. Although, the yellow dust storms are not as intense as Delhi’s pollution issues, they still disturb school activities.

School Closure or shifting online mode is the solution?

The closure of primary schools or shifting them to online mode is considered a short-term, effective solution to tackle Delhi’s air pollution. However, key question remains: will the air become clean enough after a few days to no longer impact children’s health? Will policymakers or stakeholders develop a permanent solution in the near future? How long should primary schools function in online mode – a week, a month or long? And even if schools shift online temporarily, can ensure the air will be safe for children afterward?

Understanding the intensity of the issue is crucial. As per UDISE 2021-22 there are 5619 schools functioning in Delhi, in which 47,52,107 students are enrolled. Of the total schools in Delhi 2594 are primary schools. Of the total primary schools in Delhi 1626 are government schools, 45 are aided primary, 923 are unaided recognized schools. In these schools total 17,54,430 children are enrolled. Every year the health of a significant number of children is at risk due to pollution. As per the newspaper report, in 2016 the decision to close schools affected around 9 lakh students. This number has nearly doubled over the past eight years, and it is likely to increase further in future.

Indeed, the digital divide remains a great challenge in connecting every student to online education. Issues such as access and usage gaps hinder efforts to bridge this divide. Reports and studies during the COVID pandemic shows that a large number of children either don’t have the gadgets to connect online mode or they have lack of knowledge how to use it effectively. Studies conducted during the COVID pandemic have shown that 60 per cent of school children had no access to online mode. Studies also shows that children also faced the problem related to internet speed and connectivity. Moreover, many schools were also not fully equipped to provide remote learning. The recent directives from the Supreme Court to implement a hybrid educational model reveal the existence of a digital divide. The directive for a hybrid education mode is aimed at inclusive measures to ensure that economically weaker sections are not left behind. Post-pandemic, schools resumed operations and shifted back to the normal mode from online learning.

Post COVID pandemic it is quite difficult to know how much policy maker have put effort to bridge the digital divide gap particularly for the primary students or how many schools have equipped themselves to get ready for both normal or online mode of teaching. Under such situations, closing schools or shifting it to online mode once again may push many children particularly economically weaker section with situation of learning gap, reduction in learning days and restricted emotional growth. However, keeping schools running under such environment will have its negative consequences on children health.

The problem of hazardous air is not a short-term issue and it may grow severe every passing year if not acted quickly. Importantly, closing schools or shifting it to online mode for an interim period is also not the permanent solution. Addressing air pollution situation and reduce the learning loss of children requires a combined actions of stake holders, policy makers and public and community efforts.

Other measures

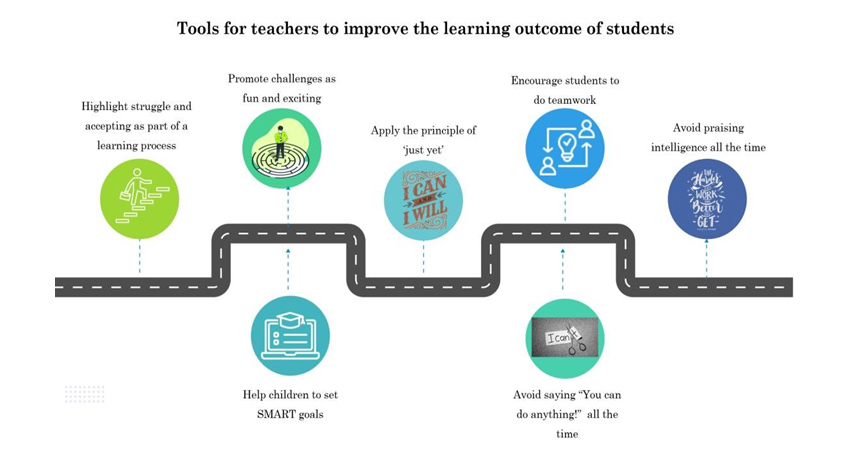

There are several other measures that are recommended during the high pollution time, thinking that these may help in protecting school children from air pollution. The few as discussed here –

i) Air Purifier: The government and institutes can equip schools and class rooms with air purifiers. The air purifier will maintain the quality of air inside the class room. This may allow the school activity to continue indoor. The indoor activity typically includes classroom learning, arts and craft session, music, dance, library and indoor games. The air purifiers solution is also implemented by China to protect school children from the harmful pollution.

ii) Limiting outdoor exposures: Schools can limit the outdoor activities and keep students indoor in the classrooms with air purifiers that can maintain the air quality during high pollution days.

iii) Installing air quality monitor devices at schools or sending alert messages so every school to limit or maintain the outdoor activities and increasing indoor activities in the class room with air purifiers.

iv) Distribution of high quality masks at frequent intervals to every students and making it compulsory to wear them while coming to the schools and returning to home.

v) Flexible Scheduling: Adjust school schedule either by avoiding peak pollution hours or by adjusting the breaks reduction in summer or autumn and providing during the severe pollution period. This will help in maintain the required number of learning days.

vi) Create green walls: Create indoor green walls or plant stations that can help improve indoor air quality naturally. Plants which help in purifying air can be planted in corridors and class windows and in school grounds such as Aloe vera, snake plant, peace lily, spider plant etc.

vii) Embed air pollution issues in education so as to sensitize children who become ambassadors and spokespersons and active members of the society to address pollution.

Case of Delhi

The current focus on protecting children from hazardous air during school hours is narrow and insufficient, failing to address the broader and more pervasive issue. Even when children are at home, they remain exposed to toxic air, a reality that is particularly alarming in a city like Delhi, where only a small fraction of households can afford air purifiers. This leaves the vast majority, including over 16 lakh students from slum areas attending government schools, vulnerable to the continuous assault of polluted air. For these children, neither their homes nor their schools provide a truly safe environment.

Frequent and unplanned breaks can lead to prolonged absenteeism among children, which, in turn, affects their interest and focus on education, especially at the foundational stage. This lack of engagement can escalate the issue of dropouts. Such circumstances can hinder the efforts of policymakers striving to bring meaningful changes to the education system. Additionally, the budget allocated for improving Delhi’s school and initiatives like teacher training to bridge learning gaps may not be effectively utilized if absenteeism or dropout rates continue to rise.

Moreover, if schools remain closed, many children, particularly those from economically weaker sections of society, will be deprived of mid-day meal facilities, which may be the only reliable and daily nutritional source for them. This reality underscores the urgent need for a comprehensive approach to tackle air pollution that extends beyond the confines of school campuses and addresses the health and well-being of children in every aspect of their daily lives.

Apart from health concerns, the frequent closures of schools or the switch to hyper-mode operations may negatively impact children, particularly those from lower- and middle-income families. The hazardous pollution situation is likely to worsen every year if core issues are not addressed, leading to learning loss and increased dropout rates, as seen during pandemic lockdowns.

Strikingly, every winter, the implementation of the Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) becomes essential to control pollution. Under GRAP, many restrictions are imposed, such as barring the entry of trucks into Delhi and older diesel heavy goods vehicles (HGVs) and halting construction activities in the capital. These restrictions adversely affect the earnings of people working in construction, transport, and allied sectors.

In such situations of income loss, middle- and low-income families are forced to prioritize basic essentials over education. There is also the possibility that, as pollution intensifies each year, many construction workers may reverse migrate or relocate to other places for better earning opportunities. This migration, whether circular or permanent, could lead to increased dropout rates.

Additionally, the worsening situation may contribute to higher rates of child labour, early marriages of girl children, and an increase in the number of “nowhere” children. These potential outcomes highlight the need for a holistic and sustained approach to combating air pollution that considers its social, economic, and educational repercussions.

Conclusion

The recurring issue of air pollution in Delhi, particularly during the winter months, poses significant challenges for schools, students, and their families. While temporary measures like school closures or shifting to online education offer immediate relief, they are not sustainable solutions. The digital divide, loss of learning opportunities, and health risks associated with pollution disproportionately affect economically weaker sections, worsening educational and social inequalities. A comprehensive approach is essential to safeguard the well-being and future of children, emphasizing both immediate mitigation and long-term systemic changes.

Suggestions for Policymakers

- Implement Long-Term Pollution Control Measures: Conduct research to find out the causes of pollution and how to address those issues for permanent solution.

- Ensure Nutritional Security: Continue mid-day meal programs during school closures by delivering meals to students' homes or community centres.

- Strengthen Social Safety Nets: Support families economically affected by pollution-related restrictions, mitigating risks of child labour and school dropouts.

These actions require collaboration between government agencies, civil society, and community stakeholders to ensure the safety and development of children while addressing the root causes of pollution.